When we start out on a Landmark project to rescue a historic building, we are typically standing in dusty spaces, surrounded by crumbling masonry and dingy timbers. Nowhere more so than at Calverley Old Hall in Leeds, a much-evolved manor house lived in for 800 years in many different guises. Though a Landmark let has thrived in one part since the 1980s, most of the rest has been standing weathertight but gutted and empty, cavernous medieval blocks quietly awaiting their next incarnation.

Landmark has now embarked on the delivery of that new purpose in an exciting repair and conversion scheme about which more can be found out here. Inevitably, focus has tended to fall upon the stunning great hall and earlier solar/hall block, but tucked behind the solar block is what today seems just a little cottage, its bedrooms plain, plastered rooms.

And it is behind the 19th-century plaster in one of these rooms that we have made a truly astonishing discovery. We have found a complete scheme of mid-16th century wall paintings across three walls of the original chamber. This is in itself an important discovery: although most vernacular houses above even middling status had some kind of painted decoration on their walls from about 1570 to 1650, such survivals are very rare, especially in northern counties and especially covering entire walls.

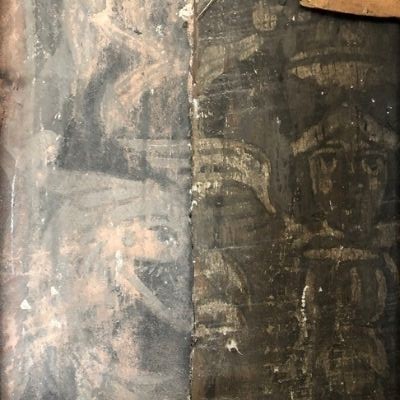

The bedroom where the paintings were found, and what was discovered beneath the plaster.

The bedroom where the paintings were found, and what was discovered beneath the plaster.

Even more exciting is that the Calverley scheme is so-called Grotesque work. It is a great deal more sophisticated than almost any other surviving domestic wall paintings in the country, and certainly than any known to date in Yorkshire.

Suddenly, we are transported from a dusty, dilapidated building into the rich and cultured world of the Elizabethan Calverleys, a well-educated family keen to display their learning and wealth by demonstrating their appreciation of Renaissance culture. The Calverley paintings are very carefully planned, in a vertical design that uses the timber studwork as a framework. Teethed birds laugh in profile; the torsos of little men in triangular hats sit on vases or balustrades. When the fantastical figures and architectural elements are incorporated into dense vertical stacks as at Calverley Old hall, they’re known as ‘candelabra.’

Teethed birds and human figures.

Teethed birds and human figures.

Around the cornice runs a frieze of Tudor roses and pomegranates. A pomegranate was an emblem originally associated with Henry VIII’s first wife Katherine of Aragon and so with her Catholic faith, perhaps significantly for the Catholic Calverleys. The design is executed in red, white and black. The whole chamber was probably originally covered in the scheme, a rich, dark, private space that must have been all the more impressive by candlelight.

A frieze of Tudor roses and pomegranates.

A frieze of Tudor roses and pomegranates.

The style is called Grotesque after the Italian word grotteschi, meaning literally ‘from the grotto’. In the 1480s, a young man tumbled down a cleft while exploring a hillside in Rome. He fell, as he thought, into a cave or grotto and had to be rescued by his friends. Exploring further by torchlight, they found they had discovered not a cave but the glittering interiors of Emperor Nero’s buried Domus Aurea or Golden Villa, built in the 1st century CE. So infamous was this emperor that his successors buried his summer palace, part of the attempt to blot out the memories of his excesses.

From then on, visitors were lowered on ropes with torches, to hang suspended and wonder at the strange Roman decorations of fantastical beasts and scrolling curlicues of foliage that danced across walls and ceilings, transported back to the lost world of Ancient Rome. You can still visit today, although now on foot in hard hats, with humidity strictly controlled.

One of the palatial chambers in Emperor Nero’s Golden Villa.

One of the palatial chambers in Emperor Nero’s Golden Villa.

Examples of ‘grotteschi’, figures and festoons in a fresco in Nero’s Domus Aurea.

Examples of ‘grotteschi’, figures and festoons in a fresco in Nero’s Domus Aurea.

Such decoration became an integral part of the later Italian Renaissance and can be seen in the frescoes in many of Palladio’s villas, the Uffizi Palace and so on. Later, in 18th-century Britain, such designs danced their way into the interiors of architect Robert Adam, newly returned from his own Grand Tour of Italy, his designs taking Britain by storm from the 1760s.

How did such work come so early to Calverley Old Hall? Certainly Henry VIII’s court knew and appreciated the new Renaissance style, and Landmark has examples of it in the finely moulded 1520s terracotta window frames at Laughton Place. However, after Henry VIII’s break with Rome in the 1530s, all things associated with Rome became highly suspect. Far fewer English now travelled to and from Italy. But style has ways of crossing frontiers.

Consequently, Renaissance design found its way to Britain through the 16th century chiefly through prints and engravings, produced by Germanic and Low Country artists like Hans Vredeman de Vries and Lucas van Leyden. Such print books were not only owned by the commissioning classes but also circulated widely among artisans in many trades, borrowed and adapted for furniture, gold and silver plate, jewellery, embroidery – and interior decoration.

It is probably from such print books that the unknown painter who decorated the wall at Calverley Old Hall drew his inspiration.

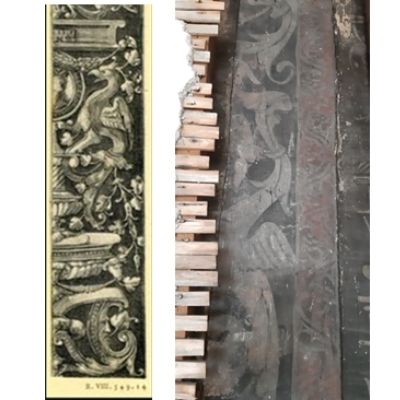

A print by Nikolaus Wilborn published in 1534, and a detail of one of the Caverley candelabra.

So who might have commissioned these wonderful paintings? The dendrochronology suggests that the roof (and therefore main structure) of the block was built 1514-39. The block had two phases (perhaps beginning as a stair turret) and its floor was inserted later, between 1547-85. This is a tantalisingly wide span of dates that covers a multitude of national and family events. The archaeology currently suggests the later period for the paintings – but even that is excitingly early.

At the moment, the most likely person to have commissioned the painted chamber seems to be Sir William Calverley (c. 1500-1572). He was knighted in 1545, and became Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1549, a man of high estate and important affairs. We believe that the painted chamber was only ever reached at first floor level from the family’s private rooms and had its own private access directly onto the gallery of the family chapel. Perhaps it was Sir William’s privy chamber, where he entertained only his closest friends and associates. Or perhaps it was his second wife, Elizabeth Sneyd’s private parlour, a refuge from vigorous Sir William’s seventeen offspring.

We’ve drawn up a specialist programme of investigation and recommendations for conservation and may well find out more about the paintings’ origins. What is already clear is that Landmark has to find a way to conserve and if possible display this miraculous survival from the Elizabethan age, a discovery that so magically transforms our appreciation of how lives were lived on this ancient site.