Printed curtains are a longstanding Landmark tradition, established by co-founder Christian Smith during the charity’s early years. Finding it difficult to source suitable fabrics for her interior schemes, Lady Smith began hand-printing textiles with a motif based on some element of each building’s history or architecture. The resulting curtains have a charmingly homespun feel and have become synonymous with Landmark over the years. Lady Smith printed her last pairs in 2012, and since 2018 I have been delighted to revive this integral part of the organisation’s heritage.

Lady Smith screenprints a set of curtains

Lady Smith screenprints a set of curtains

There has been a common approach to our textiles from the beginning. The patterns are printed in a single colour, and are always produced using a small screen repeated horizontally and vertically across the fabric. These methods demand a certain simplicity and boldness in design which I aim to honour in my own patterns. I love how these characteristic elements combine to form a unique interpretation of each building, often acting as a puzzle for its occupants to decipher during their stay.

In regards to matching the furnishings schedule, throughout the curtain development process I am in close consultation with John Evetts, Landmark’s furnishings consultant, who creates the decorative schemes for all our buildings. Colours are chosen to compliment other soft furnishings and paint colours, or in plainer interiors can be decided more spontaneously. The design itself is normally developed independently from any other decorative elements, but sometimes common threads are revealed when furniture and curtains come together. In a happy accident at Llwyn Celyn, Landmark’s mediaeval farmhouse in Monmouthshire, some of the carved oak pieces John had sourced were reminiscent of the ‘Handful of Holly’ pattern I designed for the bedrooms and bathrooms.

The 'Handful of Holly' curtains at Llwyn Celyn in Wales.

The 'Handful of Holly' curtains at Llwyn Celyn in Wales.

The method I use is screen-printing, keeping as true as possible to the practice established by Lady Smith for Landmark’s curtains. Once the design has been developed and finalised on paper, I apply it to a 20” x 24” screen by either a hand-painted or photographic exposure technique. Both of these essentially create a stencil on the mesh, through which ink is drawn using a squeegee. I print each curtain length individually rather than as a continuous length, moving the screen horizontally and vertically across the fabric to create the entire pattern. All alignment is done by eye, sometimes leading to idiosyncrasies which lend character to the finished piece. Once the fabric is printed, washed and dried I then sew the curtains, primarily by hand for the best finish.

A longstanding interest in ruined buildings led me to find inspiration in the work of John Piper, Alexander Creswell and photographer Simon Marsden who all explored this subject. Another is painter Ed Kluz, whose exhaustively researched and meticulous representations of lost houses are compelling in their jewel tone palettes. Thinking about fellow printers, I am fascinated by design duo Phyllis Barron & Dorothy Larcher who decamped from London to the Cotswolds in the inter war years to establish their cottage industry in hand printed textiles, using a combination of geometric and organic elements which typify their partnership. Peggy Angus is another 20th Century printer whose life and work I am currently enjoying reading about.

The very nature of working on a small scale helps to make my practice quite sustainable. There is almost no waste in my process as each length of fabric is printed individually and used in its entirety with no offcuts. My curtains are very much made to last and so there is a longevity in the product which goes a long way towards Landmark's sustainability mission. I also continue to explore new sources for my materials which can help to reduce my environmental impact even further.

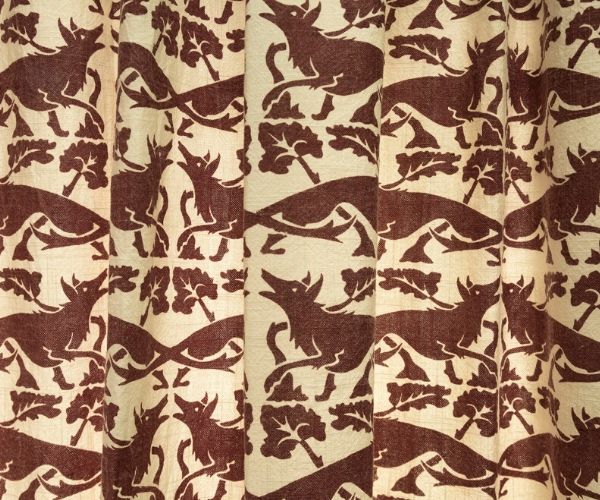

‘Wood of the Wolves’ is my favourite design which was created for Coed y Bleiddiau in Snowdonia. This was my first design for Landmark, so named from the legend that gives this humble little cottage its name; that the last wolf in Wales was killed on the surrounding hillsides. Working solely from this romantic concept rather than any strict visual references meant I enjoyed a freedom of imagination in developing the design, and I feel the outcome sits very well in its wild setting. Many of my favourite Landmark designs are those which use animals as their motif, so it was really special to be able to make my own contribution to this collection.

'Wood of the Wolves' curtains can be found at Coed y Bleiddiau in Wales.

'Wood of the Wolves' curtains can be found at Coed y Bleiddiau in Wales.

My most recent design project was for Cobham Dairy in Kent, where I printed curtains in the manner of the blue and white Delft tiles used in other dairies of a similar period. The design features the figure of a milkmaid, taken from an early 19th Century catalogue of rural dress, with a cameo of the dairy in the background evoking the pastoral scenes of Toile de Jouy. On alternating tiles, ‘the cat that got the cream’ licks its paw beneath a crescent moon borrowed from the Darnley coat of Arms. It is a playful pattern which I hoped would honour the fanciful nature of the building.

'The cat that got the cream' curtains at Cobham Dairy in Kent.

'The cat that got the cream' curtains at Cobham Dairy in Kent.

Since Cobham I have been reprinting some old Landmark designs to remake curtains which have worn out over 30+ years hanging in their properties. The need to replace those at Swarkestone Pavilion in Derbyshire offered the opportunity to reinterpret Lady Smith’s original lion rampant motif, lifted from a carving on the front of the building. I rearranged its elements to create a denser pattern with more impact in the building’s main sleeping and living space; a project which was particularly satisfying to see to fruition.