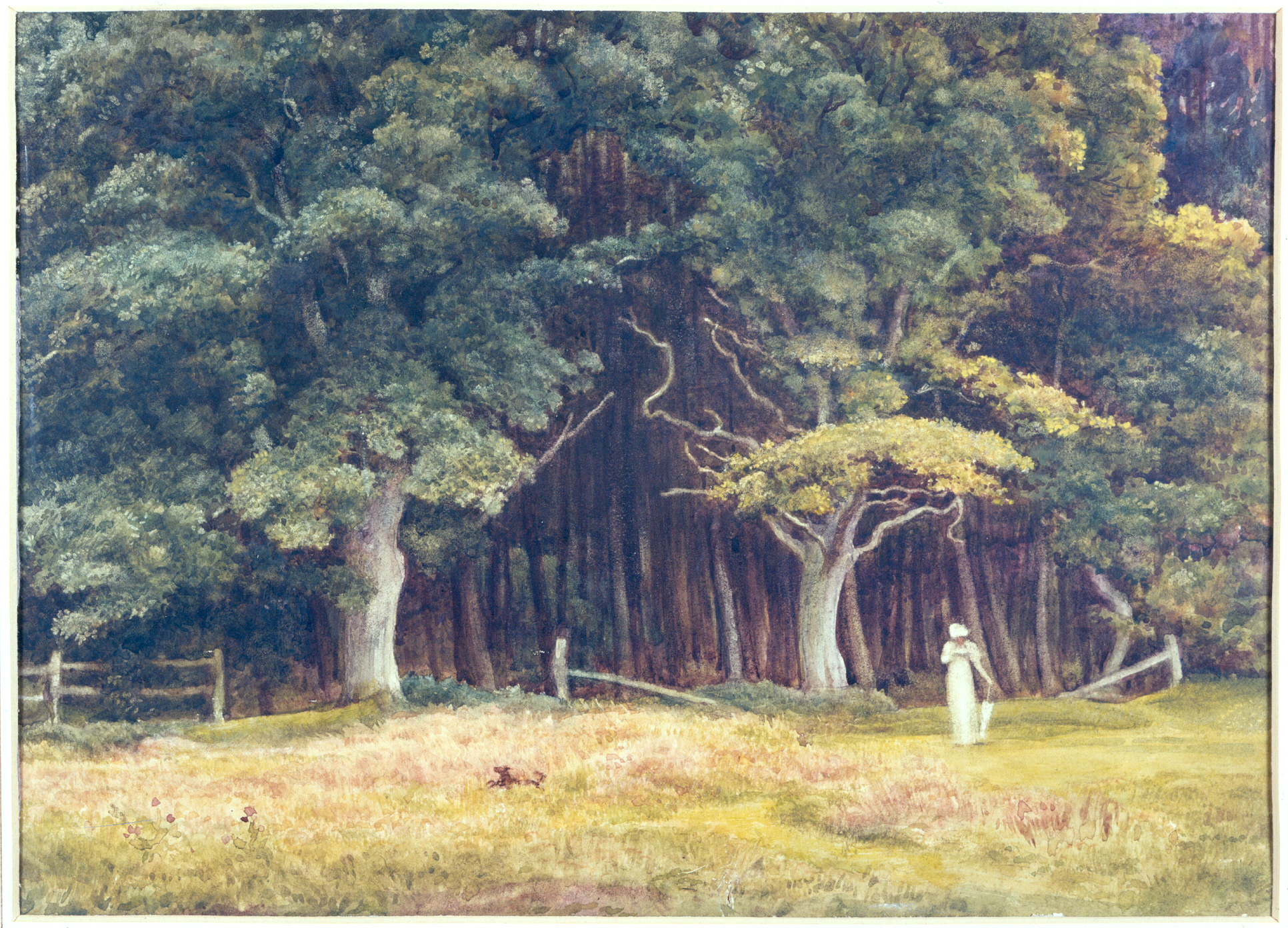

George Price Boyce (1826–1897) At Binsey, Near Oxford, 1862, Watercolour and ink on paper, Higgins Bedford.

George Price Boyce (1826–1897) At Binsey, Near Oxford, 1862, Watercolour and ink on paper, Higgins Bedford.

My research on 18th and 19th-century British art has made me very aware of the pleasure people get from trees. Woodlands make a huge contribution, both to physical health and to emotional, psychological and spiritual well-being. So while I was working on a book on this topic it seemed only natural to take holidays in woodland settings. Luckily, my family appreciated them too.

A few years ago we had a delightful Christmas in Danescombe Mine, deep in the woods around Cotehele in Cornwall. Trees grow all around the building, and the top bedroom, with its wall of windows, does indeed feel like living in a tree house. Singing carols in the Great Hall of Cotehele House, under the famous Christmas Garland, was one of the high points of the holiday. But another was taking a train into the George and Charlotte copper mine at Morwellham Quay, a short drive away. We spent cosy evenings reading about the harsh realities of 19th-century mining, in the elegant conversion of a building that once held a huge pumping engine. The evocative smell of woodsmoke from our wood-burning stove made it all the easier to imagine ourselves back to a time when the woods were places of industrial labour, echoing to the sounds of roll crushers and hammers, punctuated by shouts from overseers and their workforce.

Danescombe Mine in the woods around Cotehele, Cornwall

Danescombe Mine in the woods around Cotehele, Cornwall

On another holiday, in Swiss Cottage at Endsleigh, we contemplated the more peaceful, ornamental role of trees in the landscape. The estate was laid out for the 6th Duke of Bedford, the dedicatee of Jacob George Strutt’s Sylva Britannica with its sensitively-etched tree portraits. This was a book that I used extensively in my research: its text is wonderfully illuminating on prevailing attitudes to trees in the 1820s. Strutt was a close friend of John Constable, whose own tree drawings are very similar to those in the book. For the future, I have my eye on Peake’s House, Colchester, as a base for visiting Constable country.

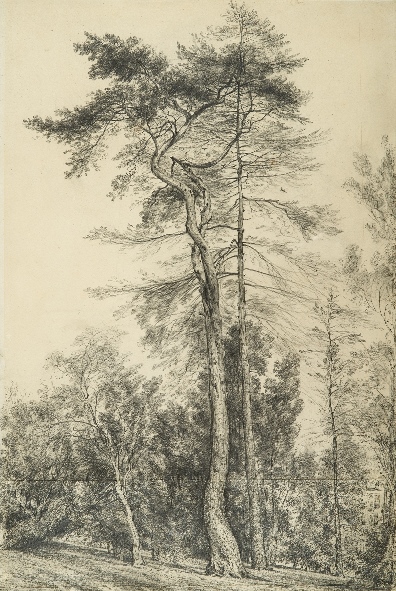

'Fir Trees at Hampstead' (c. 1833) by John Constable (1776-1837), ©Trustees of the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery (The Higgins Bedford)

From Swiss Cottage we watched the mist rising and gradually revealing the woodland around the Tamar Valley, before setting off to walk through these woods towards the pleasure grounds with their fine specimen trees. We imagined lavish picnics enjoyed by shooting parties in the sitting room. More speculatively, we thought of secret trysts in this undeniably romantic setting between the Duchess, Lady Georgiana, and the painter Edwin Landseer, who may have fathered one of her children.

Living in Swiss Cottage, you are very much aware of the use of wood as a building material. Wood cladding, still with the bark attached, has been used on the cottage to give a properly Picturesque effect. The evocative effects of wood are even more in evidence in Plas Uchaf, with its spectacular timber roof, still bearing the traces of smoke from 15th-century fires in a central hearth. My daughter is not such an avid reader of the Landmark Handbook as I am, and so she was unprepared for her first sight of the interior. I will never forget her gasp of amazement when we first opened the door to the hall. It was like entering another world, albeit one with the twenty-first century comforts of underfloor heating.

Swiss Cottage near Tavistock, Devon

Swiss Cottage near Tavistock, Devon

Landmark properties have provided strategic bases from which to see artists’ paintings and drawings, as well as the locations in which they worked. We booked the Music Room in Lancaster so that I could study John Ruskin’s tree drawings in the Ruskin Library at the University. But I am not sure which was the greater treat – seeing the drawings, or sleeping in the most exciting bedroom ever, surrounded by Apollo and the Muses, portrayed in beautiful 18th-century plasterwork. We loved the aptly-named Sun Square below the Music Room, in the heart of the city yet shaded by a venerable lime tree. A further, unexpected pleasure was the discovery of Lancaster and its hinterland, including the medieval Castle and the art deco Midland Hotel in Morecambe Bay, with its decorations by Eric Gill and Eric Ravilious.

My current research is moving outwards geographically, to encompass American painters of the early and mid-nineteenth century, looking at their depictions of trees but also thinking about their ideas and their concept of the wilderness. An important source of inspiration here was the Sugar House in Vermont – definitely my husband’s favourite Landmark. We were there in May, when the surrounding orchards were just coming into leaf, and the sugar maples still had long tubes attached to them to draw off the sap. We could think back to the days when the sap was boiled up in what was now our sitting room to make delicious maple syrup. Trees were all around us, and here again, as at Danescombe Mine, we were reminded that woods have always been places of work and commercial enterprise, as well as sites for leisure and contemplation. One day I hope to stay at Obriss Farm, Kent, which looks south over the Weald and with ancient woodland nearby. It is only a short distance from the farmhouse to Samuel Palmer’s Shoreham, and to Lullingstone Park, where you can still see the ancient oak and beech trees that the artist drew in 1828.

Samuel Palmer (1805-1881) Ancient Trees, Lullingstone Park, 1828 (copyright: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Samuel Palmer (1805-1881) Ancient Trees, Lullingstone Park, 1828 (copyright: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Evocative interludes in Landmarks provided regular respite from the research and writing of my book, Silent Witnesses: Trees in British Art, 1760-1870 (Sansom and Company, 2017). Towards the end of the research period I visited the Higgins Bedford, to see some of the watercolours and drawings from their famous Cecil Higgins collection. With the curator of the collection, Victoria Partridge, I discussed an idea for an exhibition that would coincide with the publication of my book, and also with the launch of the Tree Charter in 2017. A ten-point Tree Charter was put together by over 70 organisations under the leadership of the Woodland Trust to mark the 800th anniversary of the Charter of the Forest, first issued by Henry III in 1217. An exhibition at the Higgins Bedford, entitled "A Walk in the Woods: A Celebration of Trees in British Art" in 2018 displayed some forty watercolours, drawings and prints from the past two centuries, including works by John Constable, John Sell Cotman, Edward Lear, Samuel Palmer, Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland and Lucian Freud. The show highlighted the importance and enduring popularity of trees in art.

Everyone can buy a copy of Christiana's acclaimed book for £12.50 (RRP £25) from Waterstones here

Sir Edward John Poynter (1836 - 1919) Wooded Landscape, c1900, watercolour on paper, courtesy of the Trustees of Cecil Higgins Art Gallery (The Higgins Bedford)