In celebration of National Poetry Day, here at Landmark we wanted to reflect on how poetry relates to our work, and to our buildings.

Poetry and architecture are perhaps not the most obvious bedfellows. Poetry has tended to find its inspiration in subjects like love, mortality, and the sublimity of nature; less frequently in blueprints, cross-beams, and reticulated brickwork.

However, poetry is not some inherent quality that can be found in certain things and not in others. Rather, it is in how we look at things, and to our mind, Landmark and its buildings are ripe for the poetic eye.

Take ruins, for instance, which feature in a number of our buildings including Wilmington Priory in East Sussex, Astley Castle in Warwickshire, and most overtly, the Ruin in North Yorkshire.

The Ruin in Hackfall, North Yorkshire

Is there a more poetic emblem for the impermanence of human ambition, and the final evanescence of all things? Indeed, one of the earliest surviving poems in the English language, The Ruin, takes a set of ruins for its subject. It was written by an unknown author, probably in the 8th or 9th century. Here are the first few lines, given in both the original Old English along with a modern translation -

|

Wrætlic is þes wealstan, wyrde gebræcon;

burgstede burston, brosnað enta geweorc.

Hrofas sind gehrorene, hreorge torras,

hrungeat berofen, hrim on lime,

scearde scurbeorge scorene, gedrorene,

ældo undereotone. Eorðgrap hafað

waldend wyrhtan forweorone, geleorene,

heardgripe hrusan, oþ hund cnea

werþeoda gewitan.

|

Wondrous is this wall-stead, wasted by fate.

Battlements broken, giant’s work shattered.

Roofs are in ruin, towers destroyed,

Broken the barred gate, rime on the plaster,

walls gape, torn up, destroyed,

consumed by age. Earth-grip holds

the proud builders, departed, long lost,

and the hard grasp of the grave, until a hundred generations

of people have passed.

|

You can read the full poem with facing translation here

Haunting in its elegiac contemplation of time, loss, and death, the poem conveys ruination in more ways than one; the original manuscript was damaged in a fire, and so, just like the ruin it describes, the poem was partially ‘wasted by fate’, with some lines now ‘long lost’ along with the author that first composed them over a thousand years ago.

Of course, poetry doesn’t always have to be quite so dark and brooding. We need only look as far as that of John Dryden (with whom our Lynch Lodge has associations) for some optimism in the face of architectural devastation, perhaps more akin with Landmark's outlook and mission to save, revitalise, and preserve important buildings.

Lynch Lodge in Alwalton, near Peterborough

His poem Annus Mirabilis (Latin for Miraculous Year) was written in the wake of the Great Fire of London, which, by some estimates, destroyed around 13,000 houses, and left as many as 70,000 out of the City’s 80,000 inhabitants homeless. Dryden could well have written a despondent elegy along the lines of The Ruin, but, as his poem's title suggests, where he might have found disaster, he instead saw a miracle in the restoration and rejuvenation of the City, which he extols in these stanzas:

Me-thinks already, from this Chymick flame,

I see a city of more precious mold:

Rich as the town which gives the Indies name,

With Silver pav’d, and all divine with Gold.

Already labouring with a mighty fate,

She shakes the Rubbish from her mounting Brow,

And seems to have renew’d her Charters date,

Which Heav’n will to the death of time allow.

The Great Fire of London, 1666

One of the only houses in the City of London to survive the Great Fire is 41 Cloth Fair, now enclosed in a row of Georgian houses, two of which are Landmarks. One of them - 43 Cloth Fair - was the London home of the much-loved broadcaster, writer, and poet Sir John Betjeman, who campaigned tirelessly for the preservation of architectural heritage.

Cloth Fair, London

Indeed, many of our Landmarks are associated with some of our country’s most renowned poets. Howthwaite in Cumbria is situated just below Dove Cottage, the Lake District home of William Wordsworth, where he composed some of his best poetry. Piazza di Spagna in Rome is the apartment immediately above the one where the poet John Keats was taken by his friend Joseph Hearn to recuperate from TB, but where he died, tragically young, just a few months later. Collegehill House near Edinburgh, which was for many years an inn accommodating visitors to the famous nearby Rosslyn Chapel, boasts an impressive array of poetic travellers, including Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson, Wordsworth, and Scotland’s foremost poet, Robert Burns.

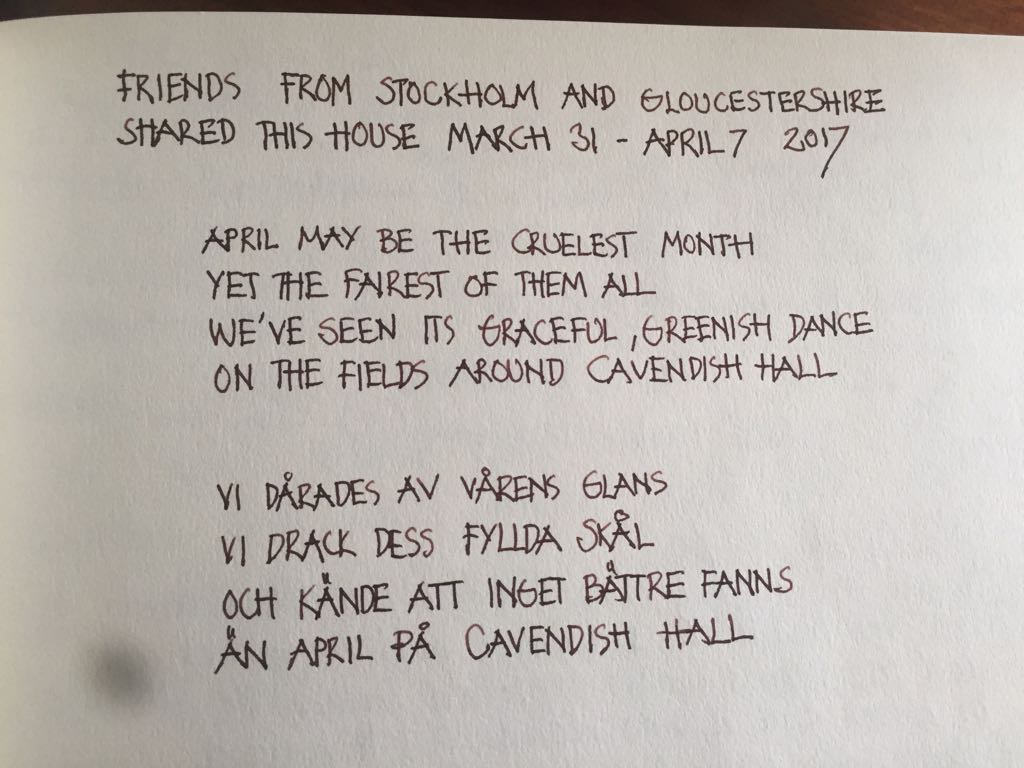

Today, our buildings continue to offer the time and space for poetic inspiration, the fruits of which we delight to find left in our logbooks from time to time. We leave you with a poem (in both English and Swedish) written by some recent visitors to Cavendish Hall -