The lovely carol known Edi Beo Thu Hevene Quene (Blessed be you, heavenly queen) was written down in Old English in the second half of the 13th century. It is also known as the Llanthony Carol, something that will make the ears prick of anyone interested in Landmark’s current project to restore Llwyn Celyn in the Llanthony Valley in Monmouthshire.

Llwyn Celyn stood on the estate of Llanthony Priory, also known as Llanthony Prima, which was founded by a Norman knight, William de Lacy, in 1105. The priory became established but was then attacked by restless Welsh natives in 1135, and its Augustinian canons fled to Gloucester, where they set up a daughter house called Llanthony Secunda. The two priories continued in union until 1205, when more peaceable times allowed for formal separation again, even though links were maintained.

Llanthony Prima, dedicated to St John the Baptist. The priory was largely built by the early 1200s and this simple tune must once have filled the now ruined nave and echoed around its cloisters.

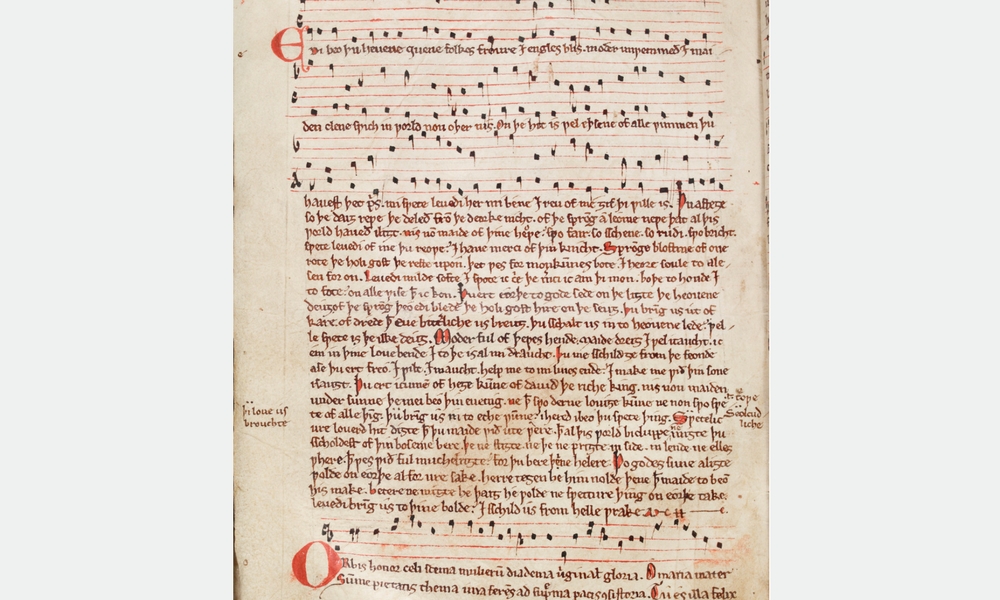

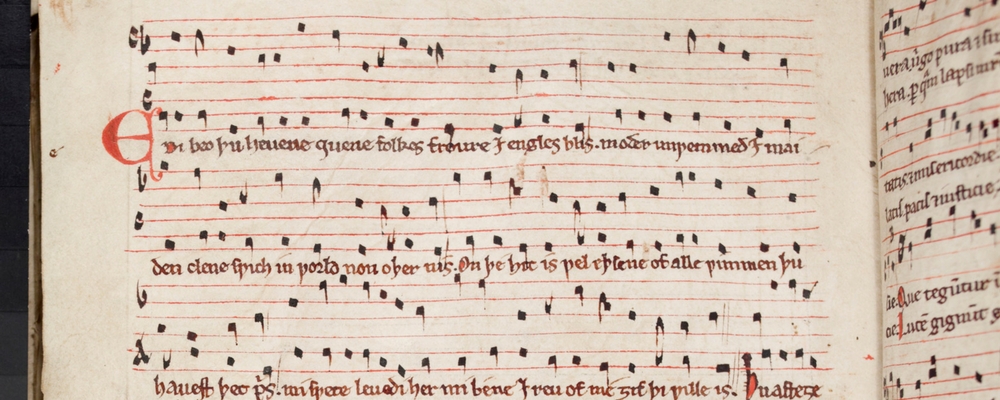

The carol surfaces in a book that once belonged to the library of Llanthony-by-Gloucester and that now belongs to Corpus Christi College, Oxford). As so often, this battered volume of 120 sheets of parchment consists of various manuscripts and shorter works bound up together into a single book. The carol is on the first (v.113r) of seven leaves bound right at the back, where the script is earlier than the rest of the book, and 13th–century in style. It is probably a record of an already well established song. On these last seven leaves especially, but also other sections, the pages have a surprising amount of ‘plummet’ or writing in lead, unusual in such manuscripts treasured as fair copies.

The manuscript for Edi Beo Theo. The two parts are transcribed at the top, and then verses written below, a red capital letter denoting the start of each. (MS CCC.59/v.113r, with thanks to Corpus Christi College, Oxford for permission to reproduce).

Books wander, and so establishing its provenance to Llanthony-by Gloucester was important. The carol is one of several hymns in the book, which also includes a long catalogue of diseases, grammatical exercises, verses in honour of St Kineburg and an epitaph for ‘Humphrey the Good.’ This Earl of Hereford died in 1275 and was buried before the high altar of St Kineburg’s chapel at Llanthony-by-Gloucester. It seems, then, that it is the book of a medieval schoolmaster who taught boys in the grammar school attached to the priory.

And we can further date the book by its dedication, which cheerfully mingles pidgin Latin and Old English:

Rex regnum, riche kink King of kings, rich king

Lux dux princeps ouer al thing Leader of light, prince of everything;

ffre Cuntis suete thing The free Countess wishes this thing of

Walterum protege Waldink Walter son of Walding,

Qui me communi librum dedit utilitat. Who gives me to be used as a book for all.

The ‘free Countess’ is Margaret, Countess of Gloucester, free referring to the time she was an unmarried widow after losing her husband at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. As she did not remarry until 1328, this dates the book’s donation to the second decade of the 14th century. The Walding family lived in Forest of Dean W of Bristol, where they held the manor of Stanton / Staunton from around 1200 (not to be confused with the Stanton-in-Gwent, a manor that abuts Llwyn Celyn).

Carols then were sung at any time of the year and not just Christmas, and this is an incredibly rare survival in the vernacular tongue (rather than Latin). Old English was spoken from the 5th to the 12th centuries (and is not to be confused with Chaucer’s Middle English).

The tune is written down for two voice parts, an alto and a soprano.

Edi Beo Thu has soprano and alto parts. Gerald of Wales, a prolific chronicler and writer in the late 1100s and early 1200s, noted that in his day such dual polyphonic singing was most found in Wales and Northumbria: ‘it was from the Danes and Norwegians, by whom these parts were more frequently invaded and held longer, that they contracted this peculiarity of singing.’ He was referring not to many parts in harmony, but just two, one ‘murmuring below. and the other in like manner softly and pleasantly above.’

This form of harmony is known to be very similar to tvisöngur (Old Scandinavian, meaning twinsong). Another contemporary commentator ‘Anonymous IV’ wrote that English singers, especially those from ‘the area known as the Westcuntre’ (ie the Marches) called thirds, rather than fifths or octaves, ‘the best consonances.’ In taking a third of an octave as its main consonance, and also in its use of the F mode with B flat, Edu Beo Thu is thus representative of an intriguing Nordic heritage that reaches still further back in time, when Danes and Vikings stalked the Marches. Such harmonisations were more often extemporised by ear than written down, so the manuscript is a rare glimpse of such early music.

And the words themselves are intriguing. The themes are Christian of course, conventional in their praise of the Blessed Virgin, the Annunciation and the virgin birth. However, the sentiments also stray beyond the orthodox Biblical themes into language found in troubadour songs of courtly love : the singer pleads ‘have mercy on thy knight’ and is lavish in praise of Mary’s loveliness. It’s also a more lively tune than might usually be associated with monastic plainsong: perhaps this catchy tune was less a carol sung by the canons of Llanthony in their own worship, than a secular song that could be danced to, or hummed joyfully through the Llanthony Valley and streets of Gloucester as people went about their work.

Landmark staff singing the carol in St John the Baptist Church at Shottesbrooke.

Today, it is known worldwide, with several versions on YouTube from as far afield as Russia. At Landmark, some of us learnt it and sang our own version in the lovely church on the Shottesbrooke estate beside our head office, a church that was itself built in the 1330s. And perhaps, even probably, the same tune was whistled a hundred years later in 1420 by the masons and carpenters who built Llwyn Celyn.

Llwyn Celyn in the snow, December 2017.