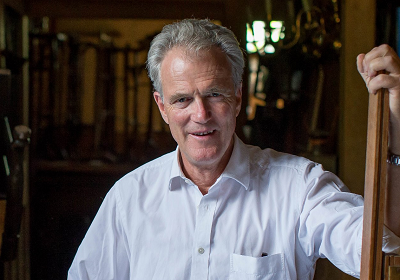

John Evetts is Furnishing Consultant for Landmark, guiding the furnishing and interiors of our historic buildings from a workshop in Gloucestershire. Here, John explains how his furnishing choices have shaped the presentation of our buildings for nearly forty years.

John Evetts is Furnishing Consultant for Landmark, guiding the furnishing and interiors of our historic buildings from a workshop in Gloucestershire. Here, John explains how his furnishing choices have shaped the presentation of our buildings for nearly forty years.

Arriving at the Landmark Trust some 10 years after it was founded in 1965 by John and Christian Smith, I found a thriving charity run from one of their buildings at Shottesbrooke near Maidenhead. Campers, as our guests were then known, were tipped off to Landmark’s existence simply by word of mouth, the first real public awareness wasn’t until a feature article in the Sunday Telegraph magazine in 1975 (which was to catch my eye and imagination). At the time John Smith was concerned that the burgeoning export of English antiques would lead to a market shortage and commissioned first Joanna Chorley and then myself to buy suitable pieces that might be useful in the future.

By 1980 we had moved the ever growing stores of furniture to the stable block at Wormington Grange in Gloucestershire and Landmark was completing upwards of six properties a year. The first on my own account was one of our Italian buildings when we had around 40 Landmarks, including 12 on the island of Lundy, but this grew over the next 30 years to the nearly 200 we manage today.

The very nature of the letting business, particularly when occupancy is upwards of the mid 80%s, is that through wear and tear, accidents and even the occasional mistreatment, furniture becomes inevitably due for replacement. We have comfortable standard upholstered chairs and sofas made to our own bespoke designs, each having two loose covers to ensure that there is always a clean set and enabling us to keep spares so exchanges are easily achieved.

Likewise with dining chairs, rather than risking the value of a long set, we buy certain models of chairs which, through experience, are known survivors and make up harlequin sets, plus we put additional ones in the bedrooms to ensure that there is always a sound collection around the dining table. Where appropriate we try not to encourage meals from polished tables as these soon become ringed and grotty, rather we provide large scrubbed-top kitchen tables roomy enough for both preparing food as well as eating.

The dining hall in Castle of Park, Glenluce

The dining hall in Castle of Park, Glenluce

I find the easiest way to visualise a room is by putting the largest pieces in first, either in one’s mind or on the floor. In the bedrooms, the beds of course take up the most room. Over the years we have settled on a firmer mattress on a hard top base which are manufactured specifically for us and which we change every 10 years or so. Using only 3’ or 5’ beds we sit them in bedsteads, usually made early in the twentieth century by Heals or manufactured in our workshop from convenient lengths of panelling.

We can make a statement about the flavour of the room while rendering the rooms simply furnished: somewhere to hang your clothes (hooks if space is lacking), a plain anonymous chest of drawers, two pot cupboards and bedside lights, a chair, a towel rail, a mirror and a few pictures - job done. “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful”… to quote William Morris, continuing …“or believe to be beautiful”. I try to ignore the latter, hoping that our visitors bring something of their own to the buildings for the few days in which they inhabit the building, and so I like to leave empty spaces in which they can position them.

Endless time and thought go into the designing and presentation of Landmarks, trying to make them legible, pleasant, convenient and uncluttered. This applies to the exteriors just as much as it does to the interiors: plumbing, wiring and heating are all kept as inconspicuous as possible, while the grounds are kept as minimal and low maintenance as practicable so that the building can be read and appreciated without distractions.

Furnishing a small space at the tiny St. Winifred's Well in Woolston

Furnishing a small space at the tiny St. Winifred's Well in Woolston

Inside, I try not to impose my own character and taste - while not denying that I furnish every Landmark as if it were my own, “that way at least one man will be happy” - but I do strive for an anonymous finish, not aiming to necessarily reflect any particular period or fashion. Nevertheless, it should be possible to visit any of our buildings and to recognise immediately that it is one of ours. This may be because of the Shottesbrooke red paint, the buttermilk limewash, Christian Smith’s curtains, the plain linen union chair covers or even the eponymous hessian lamp shades - everything is subtly but distinctly Landmark.

Frequently I am asked where I source the furniture and pieces I put in Landmarks. Auctions of course, but not as much as you might think – I find the process long-winded, even with the internet, and not as productive today as in the past. Some auction houses are increasingly fussy about what they accept as so much is slow to sell, preferring to concentrate on either the very good or the specialist, leaving an increasing volume to house-clearance. They can also be expensive, with between 30% and 40% of the hammer price lost in commissions, so I prefer to scour the markets for goods where I can. If one spots something one can ask the price, haggle, agree and clear all in one transaction. Also, items such as bedsteads, standard lamps, bedside tables and all the paraphernalia I like to have in the store are more likely to turn up at Newark than South Kensington.

A bedroom in Howthwaite, Grasmere

A bedroom in Howthwaite, Grasmere

While prices for ‘brown furniture’ have eased, in some cases to as little of 15% of their value 20 years ago, this has mysteriously not affected anything I want to buy to anything like the same extent. The reason is, I think, because I am still looking for the same things as everyone else. Kitchen tables, stools, kitchen chairs, pot cupboards and towel rails have hardly dropped at all, while sofa and breakfast tables, large mahogany bookcases and partners’ desks, once the staples of the antique trade, have plummeted. Or perhaps because flats are increasingly smaller these are seen as luxuries and that the young simply prefer to go to Ikea? Whatever the reasons, I like to think that we are not influenced by the vagaries of taste and fashion and that Landmarks, long after I am negotiating the price of gates with St Peter, will still be recognisable as Landmarks.

This is an updated extract from an article that appeared in Listed Heritage magazine (Issue 109)