Richard Bangay and the Observatory Tower at Belmont

Richard Bangay and the Observatory Tower at Belmont

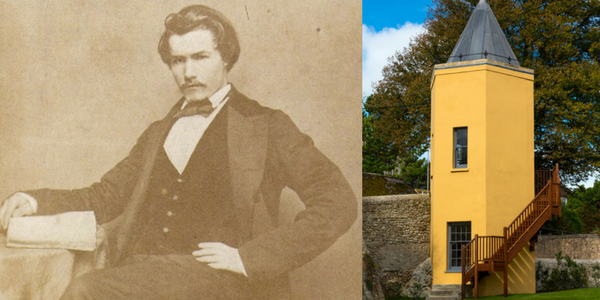

Richard Bangay was born in Sharrington, near Holt, Norfolk on November 13th 1834. His mother, Alice Bangay, was the seventh and youngest child of William Bangay who was a carpenter. Alice was a nineteen year old dairy maid and unmarried when Richard was born. The identity of his father is unknown. (On his marriage certificate of August 4th 1880 he states his father to be “Robert Bangay, farm labourer, deceased”. This was an untruth to avoid needless embarrassment).

Alice and her son stayed at the family home in Sharrington until 1844 when Alice married Henry Parnell, an agricultural labourer and lay preacher in a religious sect. They moved to a nearby village, Saxlingham but the step father treated the ten year old Richard harshly and resented the influence the local cobbler, a ‘free thinker’, was having on Richard who did not have any formal schooling.

Aged about 12 he went to work on a farm as a crow scarer, ploughboy and general labourer. By 1852 his home situation had become intolerable and at the age of seventeen Richard and his mother walked to the quay at Blakeney where he boarded a coal coaster returning to Newcastle-on-Tyne. There he found work as a pit boy at the Seaton Delaval colliery.

In his spare time he walked to Newcastle and frequented a bookshop owned by Thomas Pallister Barkas who was described as an “intellectual and author”. Under his guidance and encouragement Richard’s thirst for knowledge increased. At the shop he had the opportunity to hear famous authors read excerpts from their work. He heard Thomas Thackeray read Vanity Fair and Charles Dickens read David Copperfield. This was a long walk each way after working underground and missing a night’s sleep. His daughter, Evelyn, wrote that on one occasion he had no time to clean his lamp and was severely reprimanded.

Five years later Thomas Barkas helped Richard raise money to train as a doctor. This letter to the Duke of Northumberland asking for financial assistance describes Richard’s life since he arrived in Newcastle.

April 28th, 1858

The circumstances are as follows - a young man, named Richard Bangay, 23 years old, the son of a poor parents in Norfolk......came to this neighbourhood about five years ago to work as a collier in one of the Seaton Delaval pits. He worked down that pit for four years and for the last twelve months has been in Newcastle in the shop of a chemist at a salary of 12s a week, out of which he has to pay board and lodging etc, etc.

He has never been to school and four years ago being unable to read or write, he resolved to improve his mind.......having gained a knowledge of the alphabet and being able to read such words as to, if, so etc he took the Bible with him into the fields and by care, industry and perseverance managed with very little assistance to teach himself to read. His labours down the pit occupied about ten hours per day he allowed himself about six hours for sleep and the other eight he devoted to study. Living upon about 6s a week he spent the remainder on books instruments, and a telescope.

His progress was most rapid and was accomplished under the most disadvantageous circumstances; his only place of study being an attic with a very bad roof which let in the wind and the rain to such an extent as to blow out his candle. Under these circumstances he acquired a considerable knowledge of reading, writing, arithmetic grammar, use of globes, Latin......

Ten months ago I introduced him to Dr Embleton, lecturer at the Newcastle school of medicine who kindly granted him free admission to his lectures on anatomy and physiology.

He is quite determined to become a Medical Practitioner and in order to pay for his education in the medical school and infirmary will require £150. May I ask the favour of your Grace.......”

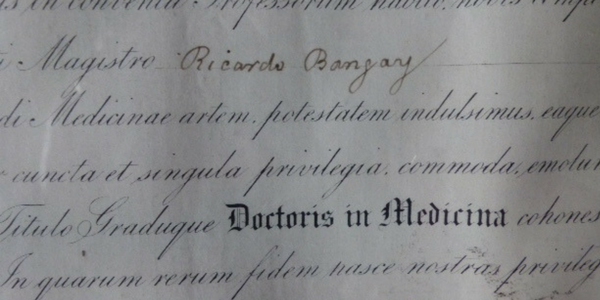

Later that year Richard duly entered the Newcastle College of Medicine where in 1859 he was awarded the 1st year Exhibition and qualified MRCS in May 1862. In 1863 he also attained an MD at St Andrews after 3 days of intensive oral examinations. For this he received a large imposing certificate in Latin.

Richard Bangay's MD certificate from St Andrews

Richard Bangay's MD certificate from St Andrews

His first medical job was in Corbridge but the past ten years of hard work and privation had taken its toll and he was advised to take a sea voyage. On February 6th he set off as ship’s doctor on the Bayswater, a sailing ship, taking emigrants to Brisbane. The journey was fully described in the weekly news sheet, the Bayswater Chronicle. There were 5 births and 3 deaths, one a 6 year old child lost overboard. Apart from his medical duties he was also the ships magistrate sentencing miscreants to a variety of minor punishments and he was also the entertainments officer, organising and giving lectures on a wide range of subjects.

After thirteen weeks of continuous sailing the Bayswater arrived at Moreton Bay. For the next four years he travelled around Australia and New Zealand and practiced medicine in Smythedale, Ballarat, Victoria. He returned to England in 1869 and became the Honorary Surgeon to the Eastern Dispensary, Bath. From there he went to a practice in Cheadle and in 1873 at the age of 39 married a widow, Bottom of Form

Margaret (Madge) Jackson who had two children, Frederick and Beatrice. Unfortunately Madge died in childbirth in 1875. The sad inscription on her tombstone reads “O my Madgie, Venio”. Richard took on the care of his two step-children and remained in Cheadle where the Dorringtons, wealthy cotton merchants, were his patients. One daughter, Bessie, had died of tuberculosis and their other daughter, Agnes, was suffering from the same disease. The treatment in those days was to keep the patient indoors and as warm as possible. Richard had advanced views in medicine and threw away all her medicine bottles, opened all the windows, halted the disease and married the patient.

In 1881 after the birth of their first child, Frank, to safeguard his wife’s delicate state of health, he sought a better climate and bought Belmont and a medical practice in Lyme Regis. Richard Bangay and his family lived in Belmont for 17 years and had 6 children despite her damaged lungs.

The census record of 1891 gives a flavour of what life was like at Belmont:

- Richard Bangay (54), general practitioner.

- Agnes Bangay(42), wife.

- Frank Bangay (10), son.

- Madge Bangay (8), daughter.

- Raymond D Bangay (7), son. (My grandfather, always known as RD).

- James D Bangay (4), son.

- Bessie Bangay (1), twin daughter.

- Evelyn Bangay (1), twin daughter.

- Beatrice Jackson (25), step-daughter.

- Frederick Jackson (27), step-son.

- Jean Green(35), cousin.

- Henrietta Dorrington (31), sister-in-law.

- Olive Dorrington (12), niece.

- Ethel Dorrington (11), niece.

- Charlotte White (24), cook

- Annie Nurcombe (21), parlour maid.

- Emma Newberry (19), housemaid.

- Elizabeth Bourman (17), kitchen maid

- Annie Parsons (22), laundry maid.

- Annie Biffin (28), nurse.

- Jessie Stephens (21), French maid.

In a cottage by the house was the gardener, his wife and children.

To support this burgeoning household Richard took on many medical roles in the town. Apart from his thriving medical practice he was also Surgeon & Medical Officer of health to the urban Sanitary Authority, Surgeon and Medical Director of the Cottage Hospital, Sidmouth Rd, Medical officer to the 1st Dorsetshire Artillery, Medical Officer of Health for Lyme Bay, Admiralty Surgeon and Agent and Medical officer to Court of the Foresters (Pride of the West). By the time he left Lyme Regis in December 1896 he had become a much loved and respected member of the community.

Richard and Agnes Bangay, Belmont 1890

Richard and Agnes Bangay, Belmont 1890

He had an excellent professional reputation in the town not least for treating the poor for no fees. The matron of the cottage hospital remarked that he was the first doctor she had seen to boil their instruments. Because of his background he was always a socialist, keen to improve the living standards of the poor and to encourage the education from which he had benefitted so much.

He initiated the Belmont Lectures which were open to all. He had many intellectual and influential friends who came to Belmont to give lectures. William Morris lectured on textile design, the great medical revolutionary, Joseph Lister, on the ‘Nucleus of a cell’ and many others of varying popular interest from ‘Birds of Siberia’ to ‘Mosquitoes of Gibraltar’.

Richard Bangay gave many of the lectures himself on botany and geology but his greatest interest was astronomy. His lectures were very popular. “Astronomy was made more attractive and instructive by the use of a profusion of diagrams, globes and experiments” said the local paper. He had built an observatory in the garden of Belmont which he used not only to look at the stars but to teach astronomy.

Before he entered the medical school in Newcastle he had worked for a year at a homeopathic chemist shop where he was employed to mix and dilute the various curative concoctions. A fellow worker was James Crossley Eno who whiled away the time making concoctions of his own and came upon an effervescent mixture that he called Eno’s Fruit Salts which to this day is one of GlaxoSmithKline’s biggest global sellers.

Richard left Lyme in December 1896 at the age of 62. He, and the members of the family he had not been able to shed, took a house in West Bournemouth for the next 4 years. He spent his time lecturing on geology, botany and of course astronomy, examining for the St John’s Ambulance Brigade as well as taking locums in Brighton, Tunbridge Wells and Kew.

In 1900 he moved again, this time to a house in Finchley, spending what little leisure hours he had making summer houses in the garden from heather and wire netting. He was never fond of children and my aunt Mary said that if she ever visited he would vanish into one of his summer houses, emerging only when the children had left.

In 1907 Agnes died and the family went their various ways but Richard remained as restless as ever, first moving to Reading with his twin daughters and then going to Canada to practice in British Columbia. His medical credentials were not valid in Canada so he returned in 1911. He was now 77 but, unwilling to retire, he returned to his roots in the mining industry and with the companionship of his daughter, Evelyn. took locums in New Tredegar and Pontypridd in the Welsh valleys.

The telescope inside Belmont's Observatory Tower, which Richard Bangay built

The telescope inside Belmont's Observatory Tower, which Richard Bangay built

At the age of 83 he took on a permanent medical post in St Helens, Bishops Auckland and after six and a half years finally retired at 90. Evelyn wrote that at St. Helens they lived in a very primitive lodging house with no running water and an outside privy but he still continued to visit the sick in the middle of the night. His very grateful patients in whom he had inspired the same respect and affection as he received in Lyme, gave him a leaving present of an up-to-date astronomical telescope “trusting that Dr Bangay be long spared to scan the stars and at the same time to think of his warm hearted friends he has left behind at St Helens.”.

Richard and Evelyn moved in with Bessie, the other twin daughter, in Chesham where he could go by bus to the museums and exhibitions of London. When Alan Cobham, the World War I flying ace, brought his aeroplane to Chesham and took customers for ‘flips’, he had one and enjoyed it so much he frequently went to Hendon for some more. At the age of 96 he was dissuaded from hiring a plane to observe the eclipse of the sun.

He died after a short illness in September 1933. His daughter Evelyn wrote in 1953:

“He had very strong socialist views and enormous energy as well as remarkably good health for most of his life. He was of fine physique and had a beautiful speaking voice with no trace of a Norfolk accent. He was buried in St, Marylebone cemetery next to Mother and Granny Alice. He attributed his longevity to much exercise, plenty of fresh air and never wearing an overcoat.”

Paul Bangay

Torridge House

Torrington

Devon